Studies have looked at individual foods such as berries, nuts, olive oil, coffee, cocoa, tea, garlic and turmeric, and their role in protecting against dementia. However, there’s not enough good quality evidence to recommend any individual food for reducing dementia risk. Rather than singling out individual foods, the priority should be to eat a healthy, balanced diet.

This page provides general information about diet-related ill-health. For individual advice, always seek guidance from a qualified health professional.

When considering the importance of good nutrition in relation to dementia, the scientific evidence shows us that:

- What people eat and drink during their lives can influence their chances of developing dementia

- A focus on good nutrition for people living with dementia can positively influence their quality of life.

In this article, we explore what the evidence tells us about diet and dementia risk and about supporting people living with dementia to eat and drink well.

Use the tabs below to jump to a section:

How diet can reduce the risk of dementia

Evidence shows that what we eat and drink can affect our risk of developing dementia. Eating a healthy, balanced diet can help to support brain function and reduce the risk of dementia in a number of ways.

A balanced diet supplies the brain with the fluid, energy and nutrients it needs to work properly. Not consuming adequate calories and essential nutrients, increases the risk of dementia and can also speed up the progression of dementia symptoms like memory loss.

The brain needs:

- Carbohydrates, which are the brain’s main source of energy

- An omega-3 fat called DHA, which is a key component of neurone cell membranes (the cell’s outer lining) in the brain

- Water, iron, iodine and zinc for cognitive processes such as learning, memory, reasoning, decision making, and problem solving

- B vitamins and vitamin C, which support brain function

- Potassium, magnesium and copper which, together with iodine, B vitamins and vitamin C, support the nervous system.

Eating a balanced diet makes it easier to reach and maintain a healthy weight, but the effect of living with obesity on dementia risk varies with age.

Research has found that obesity in mid-life is linked to a higher risk of developing dementia later on. One long-term study, tracking around 3,600 people aged 20-60 over a period of 38 years, found higher risk of developing dementia in those living with obesity at 40-49 years.

Obesity during this life stage is also associated with other health conditions that increase dementia risk, including type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol. In fact, according to The Lancet, these risk factors, together with obesity, may account for up to 12% of all cases of dementia. Read our weight loss page for advice on how to lose weight safely.

However, the link between body weight and dementia reverses in older age. Research shows that a higher BMI after the age of 70 is associated with a lower risk of dementia and being underweight in later life is linked to a higher risk. This may be due to what is known as ‘reverse causation’, where a condition (dementia) causes the weight loss, rather than the other way around. People often lose weight in the years leading up to a dementia diagnosis and this may explain why those with dementia often have a lower body weight. So, it is important to consider the relationship between body weight and dementia risk in the context of life stage.

In terms of dementia risk, in later life (e.g. over 70 years) eating a nutrient-rich diet may be more important than trying to reduce body weight.

Scientific evidence shows that what people consume throughout their lives can influence their chances of developing dementia, with one in three people born in the UK today going on to develop dementia in their lifetime.

Bridget Benelam, British Nutrition Foundation

Dietary patterns and dementia risk

While no diet can reverse or cure dementia, experts agree that eating a healthy, balanced diet can help to reduce risk factors, such as high blood pressure and cholesterol, that are linked to dementia. A good starting point is to follow the principles of The Eatwell Guide, which shows the types and proportions of foods to eat for a balanced, nutritious and sustainable diet. The main recommendations include:

- Making vegetables, fruit, wholegrains and high-fibre starchy foods the biggest part of the diet.

- Eating more plant proteins such as beans, lentils and chickpeas

- Eating less red and processed meat

- Including at least two weekly servings of sustainably sourced fish, including one oily variety, such as salmon or mackerel

- Choosing unsaturated oils and spreads

- Limiting foods high in fat, sugar and salt.

Similarly, there is also evidence that other diets, like the Mediterranean diet, which includes eating plenty of vegetables, fruit, wholegrains, pulses, oily fish, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, with some dairy products, poultry, and eggs, and limited amounts of red and processed meat, butter and sugar, can reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

A study of more than 60,000 adults included in a large UK health database found those who closely followed a Mediterranean diet had a 23% lower risk of developing dementia than those who were the least likely to eat like this.

We know that high blood pressure and cholesterol increase the risks of dementia, so it follows that diets designed to reduce blood pressure and cholesterol may help protect against dementia. The DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, for example, has been shown to be effective in lowering high blood pressure, and research suggests it may also reduce cholesterol and support weight loss - all risk factors for dementia. The diet promotes eating lots of vegetables, fruit, wholegrains, low-fat dairy products and lean protein-rich foods such as fish, poultry and nuts. This is combined with low intakes of salt, added sugar and saturated fat. Some, but not all, studies have found the DASH diet may help to slow down cognitive decline. However, more research is needed to discover whether the DASH diet can specifically lower the risk of dementia.

The MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet is a combination of the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet. It recommends 9 foods: wholegrains, leafy greens, other vegetables, nuts, pulses, berries, poultry, fish, and olive oil. It also restricts five types of food: fried foods, cheese, red meat, butter, and pastries and sweets. For each of the foods, there is a suggested number of servings per day or per week. A review of research found that strictly following the MIND diet for a period of around 5-12 years was linked to a 17% lower risk of dementia in middle-aged and older adults when compared with those who didn’t follow the diet. However, more studies are needed to draw firm conclusions on its effectiveness.

Foods

Many studies have looked at the role individual foods or groups of foods may have in increasing the risk of or protecting against dementia.

The reality is that no one food has the power to cause or prevent dementia. It is people’s eating habits and dietary patterns over many years, together with other factors such as smoking, alcohol intake and being physically inactive – that affect our risk.

Vegetables and fruit

Higher intakes of vegetables and fruit may help to lower the chances of developing dementia. One review of studies found the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia dropped by 13% for every extra 100g of vegetables and fruit consumed per day – an amount equal to slightly more than one of our 5 A DAY (80g).

More research is needed to confirm how vegetables and fruit offer protection, but benefits may be due to them containing polyphenols with potential anti-inflammatory properties, vitamins that can support brain function, and fibre which supports a healthy gut.

Fish

Eating fish has been linked to a lower risk of dementia. Fish provides many vitamins and minerals and there is plenty of evidence that eating fish, especially oily fish such as mackerel, sardines, salmon or trout, which are rich in omega-3 fats is good for overall health. A review of 35 studies found people who ate the most fish (up to 150g – about 1 large portion – per day) had an 18% lower risk of dementia than those who ate the least. This may be due to omega-3 fats in fish, which support heart health and help manage blood pressure and triglycerides – a type of fat linked to heart disease.

One omega-3 fat in particular, DHA, is particularly important for brain function. However, not all research shows the same benefits and more studies focussing on omega-3 fats and risk of dementia are needed.

Saturated fat, sugar and salt

Regularly consuming excess amounts of saturated fat, sugar and salt can increase the chances of developing health conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol which, in turn, increase the risk of dementia.

- Find tips to cut down on saturated fat.

- Find tips to cut down on sugar.

- Find tips to cut down on salt.

Alcohol

There is strong scientific evidence that high intakes of alcohol (regularly drinking more than 14 units a week) increase the risk of dementia by shrinking parts of the brain that affect memory and interfering with the brain’s messaging system.40 Regularly drinking too much alcohol also increases the risk of high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke which, in turn, increase the risk of vascular dementia. If you choose to drink alcohol, follow health recommendations and have no more than 14 units of alcohol a week, with some alcohol-free days. Find out the number of units in different drinks here.

Dementia UK has more information on the impact of alcohol.

Are there any specific foods that lower the risk of dementia?

Does our gut influence dementia risk?

Research suggests the trillions of bacteria and other tiny organisms that live in people’s guts – known as the gut microbiome – communicate with the brain and influence how it works.

Studies suggest that a poor gut microbiome may play a role in the development of various health conditions, including dementia. We don’t yet know exactly how this works, but research suggests an imbalance of bacteria in the gut microbiome may lead to chronic inflammation, which studies have suggested could increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

Studies are also starting to look at specific gut bacteria that may reduce or increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, more research is needed to fully understand how gut health affects brain health. What we do know is that eating a plant-rich diet that provides plenty of fibre provides the ‘food’ for beneficial or ‘good’ bacteria, which helps to keep the gut healthy. See our gut health section for more information.

Are ultra-processed foods linked to dementia?

High intakes of ultra-processed foods have been linked to a higher risk of dementia and also to conditions that increase the risk of dementia such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and heart disease. However, we don’t yet know what impact food processing has, if any, on the development of health conditions.

But, we do know that foods with high levels of saturated fat, salt and sugar are linked to poor health and that diets high in ultra-processed foods are often higher in calories, saturated fat, sugars and/or salt, and lower in vegetables, fruit and fibre. So, the link with poor health outcomes may actually be due an unhealthy dietary pattern. Until more research is carried out, we can’t say for sure whether ultra-processed foods specifically increase the risk of dementia. What we do know is that sticking to a healthy, balanced diet is one of the best ways to support a healthy brain.

Do diet deficiencies cause dementia?

Inadequate levels of some B vitamins can cause symptoms such as confusion or memory loss, but true deficiencies are rare in Western countries. Some studies suggest lower blood levels of vitamin B6, folate and/or vitamin B12 may be linked to a decline in cognitive function – the ability to reason, think, solve problems and make decisions.

Many studies have looked at the role supplements such as B vitamins, vitamins C and E, and omega-3 fats have in protecting against dementia. However, there’s not enough evidence to show that taking supplements helps unless a deficiency is present,. A healthy diet should provide all the B vitamins we need but, as this nutrient is found mostly in animal foods such as meat, fish, dairy and eggs, people following a vegan diet may need a daily vitamin B12 supplement.

Supporting people living with dementia

More than 1 million people in the UK care for someone with dementia. Many people living with dementia experience difficulties and need support with eating and drinking. Making sure people living with dementia stay well-fed and hydrated can be stressful – both for those with the condition and their carers.

How dementia affects eating and drinking habits

The symptoms of dementia can have a dramatic impact on a person’s ability to eat and drink well. While the type of dementia determines the difficulties or changes experienced, there are some common patterns that can impact the amount and type of food eaten. These include:

- Difficulties preparing food – poor memory, confusion, and a decline in the ability to think and solve problems can make daily tasks such as preparing food more challenging. For example, people living with dementia may find it harder to make decisions about what and when to eat. They may struggle with food shopping, planning meals, and remembering how to prepare and cook them. They may also fail to recognise ingredients and foods, especially if they are unfamiliar or look different from normal.

- Forgetting to eat and drink – memory loss can mean people living with dementia forget to eat and drink or do not remember they have already done so. They may also worry about when their next meal will be or struggle to remember foods they like and dislike. This can result in missing meals or overeating. As dementia progresses, some people may experience difficulties in remembering how to eat and use utensils.

- Challenges with coordination and movement – dementia is often associated with tremors and a loss of hand to eye coordination. This means it can be challenging to cut food into pieces, hold items such as cutlery, glasses or cups, or transfer food from plate to mouth.

- Difficulties communicating about food – some people living with dementia may find it hard to communicate that they are hungry or thirsty, and to express what they would like to eat. This may mean they miss out on meals and snacks or are given foods or drinks that they don’t like.

- Changes in behaviour around food – dementia often brings changes in behaviour, some of which may occur at mealtimes. For example, there may be a lack of interest in food, a refusal to eat, spitting food out, asking for unusual food combinations, or only wanting to eat certain things. This may cause stress at mealtimes and make it harder to have a healthy balance of foods and drinks.

- Difficulties concentrating at mealtimes – being restless, agitated, hyperactive, angry or upset are common symptoms of dementia that can make it harder for people living with dementia to sit still or focus on a meal.

- Poor appetite – a loss of appetite is common for people living with dementia due to changes in parts of the brain responsible for regulating appetite. Tiredness, constipation, depression, pain, medications, or lack of activity may also be responsible for, or contribute to a poor appetite.

- Changes in taste and smell – these senses tend to diminish as we get older, but studies suggest this often happens earlier in people living with dementia. Many people with dementia also develop a preference for sweet foods.

- Problems with chewing and swallowing – people living with dementia may forget how to chew or swallow, chew continuously, or keep food in their mouth. Poorly fitting dentures, which is a common problem for older adults and can cause discomfort and mouth sores, may also affect the ability to chew food. Studies suggest more than half of people living with dementia may experience swallowing difficulties, known as dysphagia. Alongside altering food and drink intake, this can increase the risk of choking.

- Medications – dementia medications or other medicines for conditions such as type 2 diabetes or depression can affect appetite or cause nausea or diarrhoea . It is important to speak to a GP or pharmacist if medications are affecting a person’s ability to eat well.

Nutrition plays an important role in supporting the brain - key nutrients such as omega-3 fats, B vitamins, vitamin C, and minerals including iron, iodine and zinc also play essential roles.

Research shows that healthy dietary patterns can reduce the risk of dementia, as well as reducing risk factors including high blood pressure and cholesterol, which are both linked to dementia.

Bridget Benelam, British Nutrition Foundation

Eating habits and health for people with dementia

Changes in eating habits are common in people with dementia. This can affect their intake of calories, nutrients and fluid. The risk of malnutrition increases as dementia progresses and, in turn, malnutrition can worsen symptoms of dementia. A review of studies found more than a quarter (27%) of people living with dementia in long-term care suffered with malnutrition, and more than half (57%) were at risk.

It can be extremely difficult for carers to watch a person with dementia suffering with malnutrition and, while a focus on good nutrition is advised for preserving health, it can be equally important to balance this with the sufferer’s personal preferences and quality of life for their stage of dementia. For people who are struggling to eat enough, offering their favourite foods and drinks can be the best approach, even if these aren’t strictly healthy choices.

Weight loss

The symptoms of dementia cause many people to undereat, making it difficult for them to meet their calorie needs leading to weight loss as the calories consumed from the diet are less than needed to maintain body weight.

This can be made worse if more calories are used due to constant movement caused by restlessness or agitation. Weight loss is one of the main signs of malnutrition.

Malnutrition

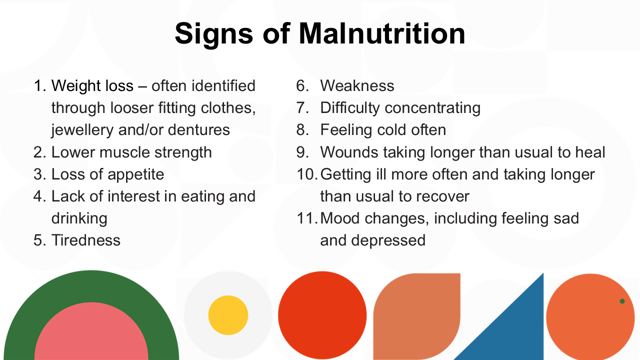

Eating less food makes it hard to get enough essential nutrients such as protein, vitamins and minerals, which can lead to malnutrition. Some of the signs of malnutrition are shown below.

Calories are needed to provide energy for the brain to function properly. Therefore, malnutrition, where there is a lack of calories and essential nutrients can lead to further decline in memory, thinking and behaviour and may even speed up the progression of dementia.

Additionally, malnutrition doesn’t just negatively affect the brain. It also weakens the immune system, making illnesses and infection more likely, and increasing the time it takes for wounds to heal. It also leads to a loss of muscle, causing weakness and frailty that makes it harder to perform everyday tasks and increases the risk of falls. Over time, the consequences of both malnutrition and dementia seriously affect a person’s quality of life.

Dehydration

The risk of dehydration increases as people get older for various reasons. The body becomes less efficient at conserving water and recognising signs of being thirsty. Medications such as diuretics, often prescribed for high blood pressure, can mean more fluid is removed from the body. Some people also drink less due to worries about incontinence or getting to the toilet in time. Symptoms of dementia such as forgetting or struggling to drink, further add to the risk of dehydration. We get fluid from foods as well as drinks and so eating less can also reduce fluid intake.

Dehydration is therefore common in people living with dementia. Confusion, poor memory, difficulty concentrating, and a reduced attention span are symptoms of both dehydration and dementia. This can make dehydration even harder to spot. Other common signs of dehydration include headaches, tiredness, a dry mouth and constipation, which can all reduce appetite and the desire to eat. Dehydration can also irritate the bladder, which worsens incontinence, and increases the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs), which can cause behaviour changes, agitation and confusion, further exacerbating symptoms of dementia.

Tips to prevent dehydration

It can be challenging to ensure people living with dementia get enough fluid to stay healthy. The amount of fluid a person needs depends on body size, gender and age, and typically varies every day due to activity levels and climate. Anything that causes sweating – such as hot or humid weather, being agitated or anxious, or having a fever – along with medications like diuretics, or illnesses that cause diarrhoea or vomiting, can lead to extra fluid losses. It’s important to replace these fluids to avoid dehydration.

As a guideline, most older women (65 years and over) should be offered at least 1.6 litres of drinks each day, while older men (65 years and over) should be offered at least 2 litres of drinks. This doesn’t have to be plain water. In fact, research suggests offering a variety of drinks based on a person’s preferences can be both hydrating and more enjoyable than always drinking water.

Try these tips to help people who are living with dementia stay hydrated:

- Offer both hot and cold drinks – this can include water, sparkling water, flavoured water, hot or cold tea, coffee, milk, milky drinks, fruit juices, soups, sports or soft drinks, and smoothies

- Use drinks to add nutrition to diets – beverages can be a useful source of nutrients, especially if appetites are poor or only small amounts of foods are eaten. Milk is a great way to add protein so offer glasses of milk, milkshakes, or hot drinks like coffee, hot chocolate and malted drinks made with milk rather than water. For even more calories and protein, mix 2-4 tbsp of dried skimmed milk powder into 1 pint of full-fat milk

- Provide preferred drinks – taste preferences can change so keep choices varied. A preference for sweet foods often develops in dementia so drinks such as a milky hot chocolate rather than coffee, or a banana milkshake over squash may be more acceptable and a good way to add calories and nutrients to diets

- Make drinks accessible – put drinks in places where they can easily be seen and reached. Regularly offer drinks with and between meals

- Ensure drinking vessels are ‘user-friendly’ – make sure cups or glasses aren’t too heavy or full and can be easily held. Lidded cups, large handles and straws may make it easier for some people. Bottles or cartons of drink that need opening may be unsuitable

- Make drinking sociable – having a drink with others is a social activity. Sharing a cuppa and a chat can make drinking more enjoyable and part of a routine that can help to encourage a greater fluid intake

- Ask your GP for advice about liquid thickeners, which can make it easier for people suffering from dementia to consume liquids

Include plenty of fluid-rich foods. Good choices include:

Savoury

- Soups

- Stews and casseroles

- Dishes with a lot of sauce e.g. Bolognese and curries

- Most fish, especially if steamed or poached

- Vegetables (most are at least 90% water)

- Mashed and boiled potatoes, and pasta.

Sweet

- Yogurt, fromage frais, rice pudding, custard

- Jelly, mousse, crème caramel and egg custard

- Fruit juice lollies

- Most fruits, especially berries, citrus fruits, melon, grapes, kiwi, mango, nectarines, peaches, pears, pineapple, plums, fruit salad, tinned and stewed fruit

- Porridge

Practical advice

Dementia is progressive and its progress can be extremely difficult for family, friends and carers to witness. Here are some tips for you to help people who are living with dementia and struggling to eat enough to maintain their weight and meet their nutritional needs. But, remember, it is better that they eat something than nothing at all. So, for example, if they only want to eat sweet things, these will be better than eating nothing.

- Take a ‘food first’ approach – offer everyday foods and drinks that are already familiar to and enjoyed by those living with dementia.

- Prioritise protein - protein in the diet, along with activity to work muscles, is important to help maintain muscle mass and reduce frailty. Good protein choices include meat, chicken, fish, eggs, milk, cheese, yogurt, beans, lentils, tofu and nuts.

- Provide full-fat, rather than low-fat foods – these are higher in calories so beneficial if weight loss is a concern. Good choices include full-fat rather than skimmed or semi-skimmed milk, butter rather than reduced-fat spread, and full-fat cream cheese rather than light varieties.

- Add more calories and nutrients to familiar dishes – ‘enrich’ or ‘fortify’ meals and snacks with other foods. For example, add dried skimmed milk powder to full-fat milk (around 2-4 tbsp powder to 1 pint of milk), then use in hot drinks and milk shakes, with cereal and porridge, or in sauces, custard and rice pudding.

- Include vegetables and fruit with meals and snacks – they provide fibre, vitamins and minerals. Add vegetables to soups and main courses, and fruit to desserts, cereal and porridge. Fresh, tinned, frozen and dried are all suitable.

- Encourage ‘little and often’ eating – offer a variety of choices to provide a good mix of nutrients.

- Provide nutritious snacks – good choices that are rich in protein, vitamins and minerals include:

- Bowl of custard

- Pot of full-fat yogurt

- Pot of rice pudding

- Cheese and crackers

- Peanut butter on toast

- Boiled egg

- Small handful of nuts

- Cheese scone with butter

- Hummus with toast

- Sandwiches filled with egg, cream cheese, salmon, tuna, chicken or beef

- Provide finger foods – especially if there are difficulties using cutlery. Alongside snacks such as cheese cubes, sliced fruit, toast ‘soldiers’, pieces of meat and sandwiches, consider main courses that are suitable for finger foods, such as potato or sweet potato wedges, homemade fish or chicken strips, chunks of omelette or tortilla, meatballs, falafel, meat and vegetable kebabs (remove the skewers), and pizza slices. Serve with nutrient-rich dips, too, such as cream cheese and chive dip, hummus, guacamole or tzatziki made with full-fat yogurt.

- Make the most of nutritious convenience foods – if food preparation is challenging, pre-prepared ingredients such as cans of fish and beans, frozen vegetables, ready-grated cheese, and pre-cooked chicken and prawns, can help to reduce the amount of effort and time needed to cook a meal.

- Consider meal delivery services – having ready-made, nutritious meals delivered can make it easier to eat well, and takes away the effort of planning, shopping and cooking every meal, while supporting independence at home.

- Adapt meal textures – soft foods may be needed if chewing is a problem. Nutrient-rich choices include eggs, fish, stews, casseroles, soups, pasta with sauce, mashed potatoes, and porridge.

- If swallowing is a problem, seek advice from your GP, who may recommend liquid thickeners to reduce the risk of choking. They may also make a referral to a dietitian or speech and language therapist who can advise on appropriate textures to reduce the risk of choking.

- Ensure regular dental checks to prevent problems such as toothache, sore gums or poorly fitting dentures, which can all affect the ability to eat.

- Promote cooking smells – the smell of cooking can help to stimulate appetite so keep the door from the kitchen open to allow smells to waft into other areas of the home.

- Add flavour to meals – a loss of taste means food may seem bland so add more flavour with garlic, spices, herbs, citrus, tomatoes, flavoured oils, pepper, and stronger flavoured cheeses. Bear in mind taste preferences might change over time, so keep offering a variety of foods.

- Offer nutritious sweet foods – there’s often a preference for sweet foods so offer those that provide more calories, protein and nutrients. Good choices include rice pudding, custard and stewed fruit, mousses made with milk, milk jelly, bread and butter pudding, and trifle made with fruit and custard. Try sweeter vegetables, too, such as sweet potatoes, parsnips, and carrots.

- Consider supplementary drinks – always speak to a health professional if there are concerns about nutrition. They may suggest supplement drinks – called oral nutrition supplements (ONS) – that help to improve intakes of calories and nutrients.

- Encourage an interest in food – this could be through talking about favourite foods, what someone ate in the past, or recalling food memories. Encourage people to get involved with helping to plan and prepare meals, setting the table and tidying up, where appropriate.

- If possible, provide vitamin D supplements – the NHS advises a 10µg supplement of vitamin D every day for adults who don’t go outside very often or who live in institutions like a care homes. This vitamin helps to keep bones, teeth and muscles healthy. It may be difficult for some people living with dementia to take pills – other forms of vitamin D such as drops that could be added to food may make this easier - talk to a GP or other health professional for advice if this is causing stress or anxiety.

For further information on helping people living with dementia visit:

- Alzheimer’s Society website

- Eating and Drinking - Dementia UK website

- Healthy Eating and Drinking

- Hydration - Ageing & Dementia Research Centre at Bournemouth University

- Eating and Drinking Well with Dementia: A Guide for Family Carers and Friends - Carers UK website

- Dementia and nutrition - NHS website - Dementia

- Age UK website - Dementia