Coconut oil has become popular as a cooking ingredient, but it is very high in saturated fat – it actually contains more than butter! Therefore, coconut oil should be consumed less often and in small amounts.

Fat

Whether you’re looking for reliable information to support your own diet or searching for science-based, nutritional insights - you're in the right place.

What is fat?

Fat is an important part of a healthy, balanced diet.

We need some fat in our diets to help us absorb the vitamins A, D, E and K. Fats are also a source of essential fatty acids, which the body cannot make itself.

However, too much fat in our diet can be bad for our health. All types of fat are high in calories and so eating a lot of fatty foods can make it easy to consume more calories than we need. Over time, this can lead to weight gain.

A diet high in saturated fat from foods like ghee, butter, coconut oil, cakes, biscuits and fatty meats, can raise cholesterol levels in your blood – this can increase the risk of severe health problems such as heart disease and stroke.

Helena Gibson-Moore, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

How does fat affect our health?

A diet high in saturated fats may:

- Raise cholesterol - too much saturated fat in our diet can raise cholesterol in our blood, which can increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

- Increase risk of obesity - because fats are high in calories, if we eat more than we need we can gain too much weight. Being overweight or obese is a risk factor for heart disease and other health related issues.

Key facts about fat

- Small amounts of fat are an important part of a healthy, balanced diet.

- Fats in foods can either be saturated or unsaturated. It is important that most of the fats we eat are unsaturated.

- The government recommends that total fat intake should not make up more than 35% of our total daily calories. On average in the UK we are achieving this.

- A diet high in saturated fats may increase the risk of obesity, heart disease and stroke.

What are the different types of fat?

Fats in foods can either be saturated or unsaturated. Most foods that contain fat have a mixture of both saturated and unsaturated fats in different proportions. We normally describe a food as being high in saturated or unsaturated fat depending on which type they have more of.

We need to be aware of the fat in our diet. For a healthy diet, it is important that most of the fats we eat are unsaturated.

Saturated fats:

Foods that are high in saturated fats include:

- Fatty cuts of meat and processed meat products like bacon, sausages, and salami

- Cheese, especially hard cheese like Cheddar

- Cream, crème fraiche and soured cream

- Butter, ghee, suet, lard

- Coconut oil and palm oil

- Coconut milk and cream

- Ice cream

- Cakes, biscuits, and pastries, like pies, sausage rolls and croissants.

- Savoury cheese flavoured crackers or twists

- Chocolate and chocolate spreads

Unsaturated fats:

There are two types of unsaturated fats: monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Monounsaturated fats are found in:

- Olive and rapeseed oils and spreads made from them

- Olives

- Avocados

- Nuts and seeds such as almonds, Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, peanuts, pine nuts and sesame seeds and spreads or pastes made from them (like nut butter or tahini).

Polyunsaturated fats are found in:

- Some vegetable oils and spreads made from them (including corn, sunflower and sesame)

- Flaxseeds, sesame seeds and sunflower seeds

- Walnuts, pine nuts

- Oily fish (including mackerel, salmon, trout, herring and sardines)

How much fat should we eat?

The government recommends that total fat intake should not make up more than 35% of our total daily calories. On average in the UK we are achieving this!

Our saturated fat intake should not be bigger than 11% of our total energy intake from food. This is about 30g per day for men and 20g per day for women.

Table 1. UK dietary fat recommendations and intakes in the UK.

|

|

Dietary recommendation |

Current average intake in UK adults |

|

Total fat |

No more than 35% total energy |

34.4% in men 35% in women |

|

Saturates |

No more than 11% total energy |

12.3% in men 12.7% in women |

Making better choices with the fats in our diets

The UK Eatwell Guide encourages us to replace saturated fat with unsaturated fat as part of a healthy, balanced diet. Foods high in fat and saturated fat such as pastries, biscuits, cakes, ice cream and chocolate are placed in a group outside of the main food groups, along with foods high in salt and/or sugars. These foods tend to be high in calories, if they are included in the diet they should only be eaten less often and in smaller amounts.

Table 2. Food swaps to save on saturated fat

|

Swap… |

For… |

By… |

|

Whole milk |

Lower fat milks like semi-skimmed, 1% fat or skimmed milk |

Using lower fat milks in tea and coffee and on breakfast cereal |

|

Cream |

Plain yogurt or lower fat fromage frais |

Add yogurt to fruit or use lower fat fromage frais in a sauce |

|

Fatty cuts of meat, processed meat products (such as sausages, bacon, burgers) |

Lean cuts of meat, lean mince, chicken without skin, fish (especially oily fish such as trout, salmon or mackerel) |

Trimming visible fat off meat before cooking

Replace some or all minced meat in cooking with beans or pulses (like lentils)

|

|

Foods roasted and fried in fat |

Foods that have been grilled, steamed, boiled, poached or baked (without fat) |

Grill meat or fish instead of roasting or frying

Steam, boil or bake potatoes and vegetables

Poach eggs instead of frying them

If you do roast or fry foods, add minimal fat and choose an unsaturated fat or oil to cook with (such as olive, rapeseed or sunflower oil) |

|

Butter, lard, ghee, coconut and palm oils |

Oils rich in unsaturated fatty acids such as olive, rapeseed or sunflower oils and spreads made with these. If you want to include these foods in your diet, do so in small amounts. |

Cook with olive, rapeseed or sunflower oils

Use unsaturated fat spreads instead of butter on bread, toast and in cooking |

|

Pastries and croissants at breakfast |

Plain wholegrain breakfast cereal or wholegrain or wholemeal toast |

Top wholegrain breakfast cereal with chopped fruit, and use lower-fat unsaturated spread on wholegrain or wholemeal toast |

|

Creamy salad dressings |

Non-creamy salad dressings (such as vinaigrette) |

Make your own salad dressings from ingredients like balsamic vinegar, lemon juice, a dash of olive oil and herbs |

How can I tell if a food is high in fat or saturated fat?

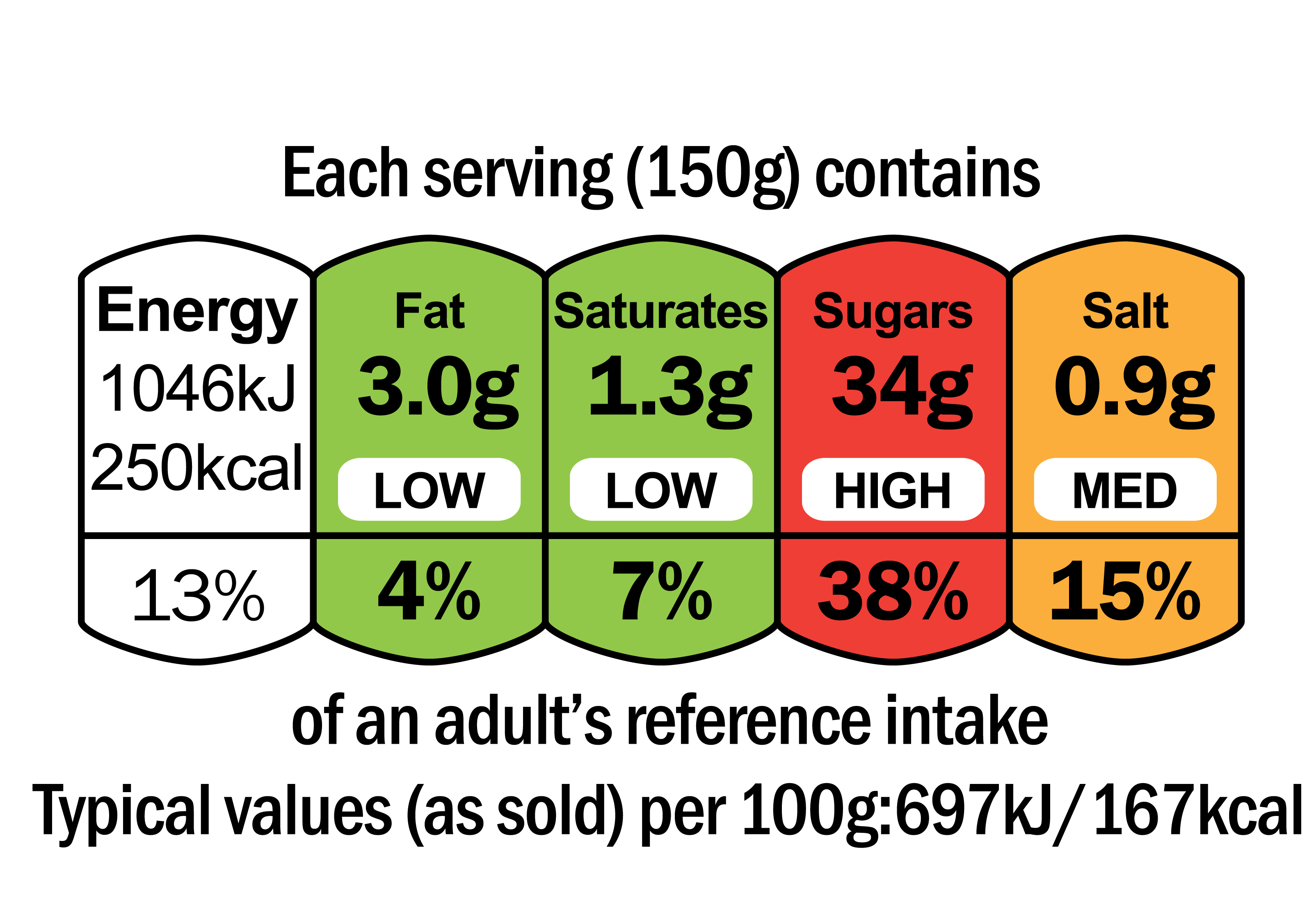

Food labels on the front of packs can be a useful tool to help us identify whether foods are high (red), medium (amber) or low (green) in fat, saturated fat, sugars and salt.

For a healthy, balanced diet, choose foods with mostly ambers or greens most of the time.

Some foods such as oily fish or nuts that are naturally high in fat may be labelled as ‘red’ for fat or saturated fat, but these are still healthy foods to include in the diet.

The label may also show the percentage (%) that a portion of the food or drink contributes to your daily Reference Intake (RI). The RI is the maximum amount that adults should have each day (see below) and is not intended as a target that needs to be met.

|

Reference Intake |

Males |

Females |

|

Total fat |

95g |

70g |

|

Saturates |

30g |

20g |

Food packaging can also show claims such as ‘low fat’, ‘fat free’, ‘low in saturated fat’, ‘lower fat’ or ‘reduced fat’. Remember that foods that are lower in fat or reduced fat are not necessarily low in fat overall. For example, if the type of food is generally high in fat (such as mayonnaise), the lower or reduced fat version may still be a high-fat food. For example, reduced fat mayonnaise contains less fat than standard mayonnaise but still has a red traffic light for total fat.

For more information on food labels read our pages on food labelling.

At a glance:

- Dietary fats provide essential fatty acids that the body cannot make itself; these become important components of cell membranes, including those in the brain and nervous system.

- Fat also carries the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K.

- Fats are a major and concentrated source of dietary energy, providing 9kcal of energy per gram, compared with 4kcal per gram for carbohydrates and for proteins.

- Although fats are often described as a single entity, there are different types of fats and each of these can have a different effect on our health.

- Fatty acids are usually classified as saturated, monounsaturated or polyunsaturated, depending on their chemical structure.

- The structural differences of fatty acids directly influence their health effects. Substituting saturated fats with unsaturated fats (polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats) lowers serum LDL-cholesterol, which is a risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease.

- Unsaturated fats are often considered to be healthy fats. Trans fats are a particular type of fatty acid. High intake of trans fats produced industrially (as partially hydrogenated oils) is widely recognised as having adverse effects on heart health.

- In the UK, saturated fats currently contribute 12.8% of food energy in adults (excluding energy intake from alcohol), which is above the recommendation of 11%, whereas average total fat intake is close to the maximum 35% of food energy recommended for the population.

- Intake of trans fats is now well below the population recommendation of no more than 2% of food energy, at 0.5%.

- In the UK, we typically eat enough n-6 fats, but intake of n-3 fats (such as from oily fish) is low.

What is dietary fat?

Dietary fats are one of the three macronutrients in our food, and are a major source of dietary energy, providing more energy per gram (9kcal/g) than protein or carbohydrates. For most people, fats are the largest store of energy in the body.

Dietary fats and oils typically contain a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, and so we usually describe a food as being high in saturated or unsaturated fat depending on the balance of fatty acids they contain. Saturated fats are typically solid at room temperature and tend to be from animal sources (such as butter, ghee, lard), as well as some from plant sources (mainly as tropical fats, like coconut and palm oil). Unsaturated fats are usually liquid at room temperature and come from plant sources (such as olive, rapeseed, sunflower, corn oils).

Fat has several important functions as a nutrient. Fat is the carrier for fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K), and is also the source of the essential fatty acids linoleic acid (n-6) and alpha-linolenic acid (n-3). Dietary essential fatty acids and fatty acids made from them are incorporated into phospholipids in cell membranes and are therefore critical components of new cell membranes.

What are different types of fats?

Most fats we eat in our diet have a similar chemical structure and are made up of three fatty acids attached to a molecule of glycerol as a ‘backbone’, known as triglyceride or triacylglycerol. Individual fatty acids can be classified according to the number of double bonds they contain:

- Saturated fatty acids (SFA): 0 double bonds (also known as ‘saturated fat’ or ‘saturates’)

- Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA): 1 double bond (also known as ‘monounsaturated fat’ or ‘monounsaturates’)

- Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA): more than 1 double bond (also known as ‘polyunsaturated fat’ or ‘polyunsaturates’)

Dietary requirements of fats

The main sources of total fat and saturated fats in the average UK adult diet can be seen in the table below, in descending order of their relative contribution.

Table 1: Sources of total fat and saturated fats in the average UK adult diet

|

|

Source |

|

Total fat |

|

|

Saturates |

|

Source: National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) rolling programme, Years 9 to 11 (2016/2017 to 2018/2019).

Dietary recommendations for saturated fat

Current government advice for saturated fat is to choose lean meats, and less processed meat and lower fat dairy products, to help reduce population saturated fat intakes. This advice reflects the recommendation to reduce population saturated fatty acid intakes in the UK to no more than 10% of total dietary energy, first made in 1994 by COMA (Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy), and which remained unchanged following a review of the scientific evidence published by the independent Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) in 2019.

SACN reviewed the totality of available evidence on saturated fats and health outcomes (more information on the report findings is provided below) and recommended that:

- The population dietary reference value (DRV) for saturated fats should remain unchanged from the previous recommendations made in 1994.

- The population average contribution of saturated fatty acids to total dietary energy (including energy from alcohol) be reduced to no more than about 10%.

- Saturated fats are substituted with unsaturated fats in the diet (mono- or polyunsaturated fats). More evidence was available supporting substitution with PUFA than substitution with MUFA.

- This recommendation applies to UK adults and children aged 5 years and is made in the context of existing UK government recommendations for macronutrients and energy.

- SACN recommended that the government considers strategies to reduce the population average contribution of saturated fatty acids to total dietary energy (including energy from alcohol) to no more than about 10%.

- It was also recommended that risk managers should be mindful of the available evidence in relation to substitution of saturated fats with different types of unsaturated fats and ensure that strategies are consistent with wider dietary recommendations, including trans.

These recommendations for saturated fat are consistent with international recommendations, including those made in the US and Australia, and by the WHO and European Food Safety Authority

Dietary reference values for fat (as population averages) were set by COMA in 1991 and are shown in the table below, with relevant intake data for UK adults (aged 19-64 years) from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme.

Table 2: Dietary reference values for fat

|

|

Dietary Reference Value (population average unless otherwise indicated) |

Current average intake (Adults, 19-64 years) |

|

Total fat |

35% of food energy (excluding alcohol) |

35.2% in men 35.7% in women |

|

Saturated fats |

11% of food energy |

12.7% in men 12.9 % in women |

|

Trans fatty acids |

Below 2% of food energy |

0.5% in men and women |

|

Total cis polyunsaturated fats |

6.5% of food energy |

No data |

|

Cis n-3 polyunsaturated fats |

Minimum intake for individuals, ≥0.2% of total energy from alpha linolenic acid. |

1.0% in men 1.1% in women |

|

Cis n-6 polyunsaturated fats |

Minimum intake for individuals, ≥1% of total energy from linoleic acid. |

5.2% in men 5.3% in women |

|

EPA + DHA |

450mg/day |

No data |

|

Monounsaturated fats |

13% of food energy |

13.1% in men 13.2% in women |

Sources: National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) rolling programme Years 9 to 11 (2016/2017 to 2018/2019); COMA (Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy) Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom report (1991). *Note that ‘food energy’ excludes energy intake from alcohol, whereas ‘total energy’ includes energy from alcohol; ** The COMA (Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy) Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom report (1991) recommended that cis-MUFA (principally oleic acid) should continue to provide on average 12% of dietary (food) energy for the population.

Current intakes of saturated fats

Although intake of saturated fats has fallen over the past 30 years, UK intakes are still above the recommended level of no more than 10% of total dietary energy (11% of food energy) for all population groups (see table below).

Table 3: Saturated fat intakes (% total energy) for different age groups in the UK population

|

|

Total saturated fat intake (% of total energy) |

|

4-10 years old |

13.1% |

|

11-18 years old |

12.6% |

|

19-64 years old |

12.3% |

|

65-74 years old |

12.8% |

|

75+ years old |

14.1% |

Source: National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) rolling programme Years 9 to 11 (2016/2017 to 2018/2019).

The UK Eatwell Guide provides guidance on the proportions of different food groups that make up a healthy diet and this can be applied to suit different dietary patterns including vegetarian and Mediterranean-style diets, which have been shown in many studies to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. More information on this topic is available on our page on the science of cardiovascular disease.

The evidence on dietary fats and health

Saturated fats

The evidence as a whole suggests that reducing saturated fat in the diet and replacing it with unsaturated fats improves blood lipid profiles (such as lower LDL-cholesterol), and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and coronary events (like a heart attack). Importantly, the evidence suggests that reducing saturated fat intake is unlikely to have adverse effects on health.

The totality of available evidence supports and strengthens current recommendations that saturated fatty acids should make up no more than 10% of total dietary energy, and that saturated fats are substituted in the diet with unsaturated fats (poly- or monounsaturated fats). Although there is less evidence available for the beneficial effects of replacing saturated fats with monounsaturated fats, there is a suggestion of beneficial effects on blood lipids.

The Mediterranean dietary pattern is lower in saturated fat and higher in monounsaturated fats and is a diet that has been associated with cardiovascular health benefits. For example, in the well-known PREDIMED trial (conducted in Spain), there was a lower incidence of major cardiovascular events among participants who followed a Mediterranean diet supplemented with either extra-virgin olive oil or nuts, compared to those assigned to a low-fat diet.

n-3 fatty acids

Since it was first suggested that the abundance of n-3 fatty acids in the diet of the Greenland Inuit people was responsible for their low mortality from heart disease, there has been considerable interest in the potential protective role of the long-chain n-3 fatty acids found in oily fish on heart health.

In the UK, government advice to consume at least two portions of fish per week (140g each), one of which should be an oily fish, has been in place since a review of the evidence in 1994 by COMA (Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy) concluded that this would likely benefit heart health of the UK population by reducing cases of coronary heart disease (CHD).

A recent systematic review of trials (published in 2020) in which people increased their long-chain n-3 fatty acid intake (for at least 12 months), it was concluded that there was limited evidence to suggest a benefit in terms of lowering the risk of cardiovascular events or cardiovascular mortality. However, the authors’ conclusions were based mainly on trials in which people consumed EPA and DHA as fish oil supplements, and they noted that there was little evidence available on the effects of eating fish. It was also acknowledged that oily fish are nutrient-dense foods, which provide other important nutrients in the diet (such as vitamin D, calcium [when eaten with bones], iodine and selenium).

The interest in the potential heart health benefits of n-3 fats has spread to encompass plant seeds and oils rich in ALA, including chia seed, flaxseed and rapeseed oils, and nuts (especially walnuts). One of the proposed mechanisms for the protective role of n-3 fats against cardiovascular diseases is via their ability to lower blood triglyceride concentration. However, in the same extensive systematic review of the evidence on long-chain n-3 fats, the authors also concluded that eating more short-chain ALA (such as as walnuts or enriched margarine) probably makes little or no difference to all‐cause, cardiovascular or coronary deaths, or coronary events.

Dietary fats as part of healthier dietary patterns

It is important to remember that we consume a variety of foods in our diets that provide a range of nutrients, and not just single nutrients like saturated fatty acids. Therefore, a ‘whole diet’ approach is important when considering the impacts of diet on long-term health. This focuses on the balance of foods consumed within the context of the overall dietary pattern, rather than individual foods, food constituents or single nutrients. Healthier dietary patterns that are associated with lower risk of chronic diseases, including heart disease have been explored in the scientific literature.

Such diets are consistently rich in vegetables and fruits, nuts, wholegrains, and include some unsaturated fats and oils, as well as a variety of protein foods, including nuts and pulses, seafood, eggs, lean meats and poultry, and some lower-fat dairy products (or dairy alternatives). They are also characterised by lower intakes of fatty/processed meats, refined grains, sugar-sweetened foods and beverages, lower salt, and lower saturated fat content. Alongside dietary patterns, there are other aspects of a healthier lifestyle, including regular exercise, adequate sleep, maintaining a healthy weight, and not smoking, which are also associated with lower risk of chronic diseases, and should also be considered alongside dietary factors.

SACN Saturated fats and health report

The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition Saturated fats and health report (2019) reviewed the evidence on saturated fats and health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and events (such as coronary heart diseases [CHD], stroke, peripheral vascular disease), type 2 diabetes, selected common cancers, cognitive impairment and dementias. SACN also looked at evidence for the association between saturated fats and risk factors such as blood lipids, blood pressure, bodyweight and cognitive function.

In summary, SACN concluded that:

- Higher saturated fat consumption is linked to raised blood cholesterol.

- Higher intakes of saturated fat are associated with increased risk of heart disease.

- Saturated fats should be swapped with unsaturated fats.

- There is no need to change current advice that saturated fat should not exceed around 11% of food energy.

Importantly, the report also found that reducing saturated fat intake was unlikely to increase health risks for the UK population. SACN recommended that the dietary recommendation that saturated fatty acids should make up no more than 10% of total dietary energy (11% of food energy) is upheld and that the advice for the public should remain as saturated fats should be substituted with small amounts of unsaturated fats (PUFA or MUFA).

However, whilst blood cholesterol, along with other ‘classical’ modifiable CVD risk factors such as smoking, blood pressure and obesity, remain influential, they are not the whole story when it comes to determining our risk of CVD. The more emerging risk factors that are also understood to play a role in heart disease and stroke were reviewed in the British Nutrition Foundation Task Force report Cardiovascular Disease: Diet, Nutrition and Emerging Risk Factors. The report explores areas including inflammation, endothelial function and platelet activity and for each of these, replacing saturated with unsaturated fats had a beneficial effect, demonstrating that the type of fat in the diet is not only important in relation to blood cholesterol.

Fats and obesity

Fat is the richest source of energy available in the diet and so can readily contribute to weight gain. As fat may also have a less satiating (filling) effect than some other food components (such as protein and fibre) it may be easier to consume an excess of energy when eating a diet with lots of foods high in fat. If energy intake and expenditure are unbalanced then any excess energy is stored in the body as fat, which may over time result in an individual becoming overweight or obese.

Low-fat diets (containing between 10 and 30% dietary energy from fat) compared to usual diets have been shown to have benefits for weight loss. Caloric restriction is the fundamental premise of a successful weight loss strategy, and evidence suggests that individuals can lose body weight and improve their health status on a wide range of energy (calorie) restricted dietary patterns with varying proportions of macronutrients.

Whether weight loss is achieved by lowering the proportion of calories from fat or carbohydrate, restricting energy intake during certain days/period of time, or using low energy meal replacements, optimising adherence may be the most important factor for weight loss success in the long term.

Nutrition labelling of fats

The labelling of total and saturated fats in pre-packed foods is mandatory under Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 on food information to consumers (FIC), a version of which has been retained and continues to apply to businesses in Great Britain following the UK’s departure from the EU.

The amount of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats in the food may also be included on nutrition labels if desired. Labelling of the trans fats content of pre-packed foods is not permitted, but partially or fully hydrogenated oils can be included in the ingredients list. However, a recently adopted EU regulation has set a maximum limit for trans fats (other than those naturally occurring of animal origin) of 2g per 100g of fat in all food products sold to EU consumers, which businesses have been obliged to comply with as of April 2021.

Nutrition and health claims on fats and oils

A number of nutrition claims are permitted for fats on food packaging. Some examples of these can be seen in the table below. A list of authorised health claims for use on products in Great Britain (England, Wales and Scotland) can be found on the Great Britain nutrition and health claims (NHC) register.

Table 4: Permitted nutrition claims relating to dietary fat content

|

Nutritional claim |

Definition |

|

Fat-free |

The product contains no more than 0.5g of fat per 100g or 100ml |

|

Low fat |

The product contains no more than 3g of fat per 100g for solids or 1.5g of fat per 100ml for liquids (1.8g of fat per 100ml for semi-skimmed milk) |

|

Low saturated fat |

The product does not contain more than 1.5g per 100g of saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids for solids, or 0.75g per 100ml for liquids. In either case, the sum of saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids must not provide more than 10% energy. |

|

Saturated fat-free |

The sum of saturated fat and trans-fatty acids in the product does not exceed 0.1g of saturated fat per 100g or 100ml.

|

|

Source of omega-3 fatty acids |

The product contains at least 0.3g ALA per 100g and per 100kcal, or at least 40mg of EPA + DHA per 100g and per 100kcal |

|

High in omega-3 fatty acids |

The product contains at least 0.6g of ALA per 100g and per 100kcal, or at least 80mg of EPA+DHA per 100g and per 100kcal |

Source: Regulation (EU) 1924/2006

Table 5: Authorised health claims for different types of fatty acids

|

Nutrient |

Claim |

|

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) |

ALA contributes to the maintenance of normal blood cholesterol levels |

|

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) & linoleic acid (LA), essential fatty acids |

Essential fatty acids are needed for normal growth and development of children. |

|

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)

|

DHA contributes to the maintenance of normal blood triglyceride levels DHA contributes to the maintenance of normal vision DHA contributes to maintenance of normal brain function DHA maternal intake contributes to the normal brain development of the foetus and breastfed infants. DHA intake contributes to the normal visual development of infants up to 12 months of age. DHA maternal intake contributes to the normal development of the eye of the foetus and breastfed infants. |

|

Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid (EPA/DHA)

|

EPA and DHA contribute to the normal function of the heart. DHA and EPA contribute to the maintenance of normal blood pressure. DHA and EPA contribute to the maintenance of normal blood triglyceride levels. |

|

Foods with a low or reduced content of saturated fatty acids

|

Reducing consumption of saturated fat contributes to the maintenance of normal blood cholesterol levels. |

|

Unsaturated fats

|

Replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats in the diet contributes to the maintenance of normal blood cholesterol levels . Replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats in the diet has been shown to lower/reduce blood cholesterol. High cholesterol is a risk factor in the development of coronary heart disease. |

Practical ways to help meet recommendations for fat intakes

Although progress has been made in recent years towards reaching population goals for intakes of some nutrients in the UK (such free sugars), intakes of saturated fats remain above the recommended 10% of total dietary energy, and analysis of NDNS data indicates that average intakes have not decreased significantly during over the 11 years of the survey (from 2008/2009 to 2018/2019).

The UK government’s Eatwell Guide recommends that foods high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS), if included in the diet, should be consumed less often and in smaller amounts.

Examples of swaps that can be made to reduce saturated fat include:

- Cooking sparingly with oils rich in monounsaturated fats (such as olive and rapeseed oil) or polyunsaturated fats (such as sunflower or corn oil), instead of butter, palm or coconut oil

- Using a lower fat spread instead of butter

- Choosing lean meat or poultry without the skin, or oily fish, instead of red or fatty meat

- Remove visible fat before cooking where possible

- Grilling or baking foods, instead of frying and roasting using small amounts of unsaturated oils, such as olive, sunflower or rapeseed oils

- Switching to semi-skimmed, 1% or skimmed milk instead of whole milk

- Choosing low-fat, no added sugar yogurt instead of cream for desserts

- having a piece of fruit as a mid-morning or afternoon snack, instead of cake or biscuits

- When using cheese to flavour a dish or sauce, use smaller amounts of strong-tasting cheese, such mature cheddar, or use reduced-fat versions

Emerging research in dietary fats

Dairy, saturated fat and health

Dairy foods are an important food group as part of a healthy, balanced diet. Food-based dietary guidelines such as the UK’s Eatwell Guide recommend that dairy foods (or fortified dairy alternatives) should make up approximately 8% of the food we consume by volume and it is recommended that we choose lower fat dairy foods where possible, such as semi-skimmed, 1% and skimmed milk, reduced fat cheeses and low-fat yogurt.

However, some evidence has shown that milk and dairy foods have neutral or protective effects on cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases, despite some products being higher in saturated fats.

The explanation behind this apparent contradiction has been suggested to be that the food matrix in dairy foods changes how saturated fat impacts on health. Dairy foods are made up of complex matrices of nutrients, bioactives and other components, such as calcium and bioactive peptides which interact with each other when consumed.

Additionally, the fat in dairy foods is found within a biological membrane called the milk fat globule membrane, which may have an influence on the amount of fat that is absorbed from dairy foods in the small intestine during digestion.

More research into the dairy food matrix will help us understand fully how the structure of dairy foods and the mixture of nutrients they contain may bring health benefits. For more information read a review on saturated fats, dairy foods and health in our peer-reviewed journal, Nutrition Bulletin.

Reformulation to reduce saturated fats in foods

A process called ‘interesterification’ is increasingly being used by the food industry to produce modified fats with different compositions and desirable functional and physical properties that can be used when reformulating food products. Interesterification uses chemicals or enzymes to rearrange the fatty acids in a triglyceride molecule, in either a random or specific way, to produce an interesterified (IE) fat with different functional characteristics, such as a higher melting point, which might be useful in certain food products.

Using modified fats, such as IE fats, has helped food producers to remove trans fats from food products without losing important aspects of functionality. More recently, it has also been used as a means of reducing the saturated fat content of food products, by providing fats and oils with similar properties but a lower saturated fatty acid content.

In the UK, IE fats are typically used in the manufacture of fat spreads, bakery products, biscuits, dairy cream alternatives and confectionery, but could be used to reformulate more products in the future to help reduce population intakes of saturated fats. Research is limited on the health effects of consuming IE fats but suggests no adverse effects on cardiovascular health. However, there are gaps in the research that require further investigation. To learn more from experts in this area watch our Fats Forward webinar.

You can also read more from a roundtable event on the subject of interesterified fats in foods in our peer-reviewed journal, Nutrition Bulletin.

Oleogels

Emerging research is investigating the potential of using edible oleogels in food manufacture as a way to remove saturated fats to develop healthier food products. Edible oleogels are liquid oils that are trapped in a 3D solid network, and therefore have more solid-like properties. Though this technology isn’t currently being used to produce foods that are on our supermarket shelves, in the future edible oleogels could be used as a replacement for solid fats containing high levels of saturated fats in food products such as chocolate, dough and pastry, fat spreads, processed meat products and ice cream.

Fat FAQs

Are dairy foods bad for my heart?

Although most of the fat in dairy foods is saturated fat, more evidence is emerging that dairy foods may actually reduce the risk of heart disease.

Dairy foods can form an important part of a healthy, balanced diet, as they are important providers of protein, calcium and other minerals such as iodine.

However, it is still recommended that we choose lower fat versions of dairy foods most of the time, such as semi-skimmed, skimmed or 1% fat milk, reduced or lower fat cheeses (cottage cheese or quark) and lower fat yogurts as these provide the important nutrients with fewer calories. Because many UK adults are overweight or obese, lower fat dairy can be important for weight control.

Does fat in the diet make you put on weight?

Foods that are high in fat are also ‘energy dense’, that is, they have a high number of calories per gram. High-fat foods can also be very tasty and both these factors can make it easy to eat a lot of calories from these foods.

If we eat more calories than we need then, over time, this will lead to weight gain. However, weight gain can be a result of excess calories from any source in the diet.

You also might like to read about:

Last reviewed October 2023. Next review due October 2026.